A judge who was “flying blind” in a conspiracy-murder trial crashed the plane, a defense attorney said.

And a Trenton man’s right to a fair trial perished when a jury, confused about how to reconcile competing legal issues, “compromised” by reaching “inconsistent” verdicts in August, according to court papers.

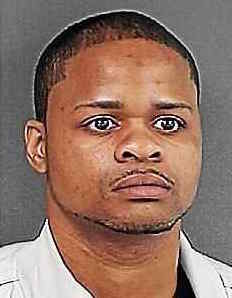

Raheem Currie

On the one hand, the jury convicted Raheem Currie of aggravated manslaughter and a gun conspiracy while acquitting him of murder and a gun conspiracy in the shooting death of James Austin, a father to twin daughters and the son of a retired city cop.

“This is legally impossible,” Furlong & Krasny associate Andrew Ferencevych wrote in court papers. “The jury concluded [Robert] Bartley and Currie did not conspire together to use the weapon for an unlawful purpose. If, according to the jury, Bartley and Currie did not share a purpose to use the weapon unlawfully against a person or property, how could Currie be guilty of aggravated manslaughter?”

Ferencevych asked a judge to set aside the guilty verdicts and give Currie a new trial, hitting on a number of points in a 30-page brief that rehashed testimony and delved into nuanced legal issues that arose at trial.

Currie’s attorneys faulted Judge Pedro Jimenez for not providing an “accurate or understandable jury charge” on accomplice liability and not controlling spectators inside his courtroom who wore “inflammatory” memorial buttons they say undermined the fairness of the trial.

About the charge, defense attorney Jack Furlong had said Jimenez was “flying blind” because of a state Supreme Court decision in State v. Bridges.

The case effectively moved the goalposts for when someone is responsible for murder when co-conspirators haven’t agreed to commit murder.

Currie and his cousin, Bartley, are awaiting sentencing for the fatal shooting death of Austin.

Robert Bartley

Austin, the son of a retired sergeant Luddie Austin, was killed Feb. 26, 2013, following an argument about who was going to pay for the bashed-out window on Currie’s car.

In admitting he shot James Austin, Bartley reached a plea deal with prosecutors to admit to aggravated manslaughter for 25 years and testify against his cousin at trial.

Currie was convicted in August, during a doozy of a trial that left almost everyone in the courtroom scratching their heads when the jury delivered its confusing verdict.

The trial itself was tantamount to a legal lecture on conspiracy and accomplice liability.

Further complicating the case, Jimenez tossed out a conspiracy to commit murder charge prior to the jury’s deliberations when prosecutors agreed there was not enough evidence to sustain it.

His decision was based on Bartley’s testimony.

Bartley said he did not intend to kill James Austin when he went, armed, to his home.

Currie and two others picked up Bartley after Currie scuffled with James Austin. They broke each other’s windows.

Bartley testified that Currie asked him on the phone if he had his gun, which he flashed at Currie and his girlfriend when he got in the car as they rode back toward the home of James Austin’s girlfriend.

Bartley kept the gun in his pocket while he confronted Austin, to try to get him to pay for the broken windshield.

Currie, his girlfriend and another man waited in the car.

Despite the testimony, Jimenez decided the jury could consider whether Currie encouraged the murder by asking about the gun, as well as other conspiracy charges.

“Why else bring a gun to a fist fight?” Jimenez said.

James Austin with his twin daughters

In the end, Currie was convicted of a lesser charge of aggravated manslaughter, conspiracy to commit unlawful possession of a weapon and unlawful possession of a weapon.

Ferencevych said the judge wrongly included lesser manslaughter charges against Currie even after he dismissed the conspiracy to commit murder charge.

Ferencevych said it was clear Currie did not conspire with Bartley to kill James Austin.

He didn’t provide the gun or plan the shooting.

Even Bartley said he didn’t intend to shoot and kill James Austin and stressed as much to detectives when he confessed to the slaying.

He contended he shot James Austin because he couldn’t see what was in his right hand.

“Our Supreme Court held it was legally impossible for a defendant to intend an unintended result,” Ferencevych wrote.

Also, Currie 's jury was not allowed to decide for itself whether James Austin's death was justifiable homicide.

“The jury should have been permitted to decide whether there was an honest and reasonable belief that deadly force was necessary for Bartley to protect himself,” Ferencevych wrote.

James Austin's relatives have worn memorial buttons like these at the murder conspiracy trial of Raheem Currie.

Ferencevych also made an issue about memorial buttons worn by James Austin’s relatives, in front of jurors.

The buttons had photos of James’ twin daughters, along with a message decrying gun violence: “Our daddy missed out first steps because of guns.”

Jimenez denied a defense’s request for a mistrial based on the button issue.

Ferencevych asked the judge to reconsider.

“It was impossible for a jury to calmly weigh the evidence without considering the implicit biases that were present in the courtroom on a daily basis during the trial,” he wrote.